Yarnell Street seems like any other suburban neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley.

The east side of the Sylmar, California, road features two one-story homes – a blue-trimmed white house with a minivan out front and an orange house with a hedge and American flag.

But on the west side of the street, behind a clay-colored fence, wild animals thrive in their oasis.

The fence leads down a dirt driveway lined with silver olive trees, whose black fruits lie smashed at our feet, pits oozing out of the skin. At the end of the drive, a plastic iguana sits on an old tree trunk, foreshadowing the critters to come.

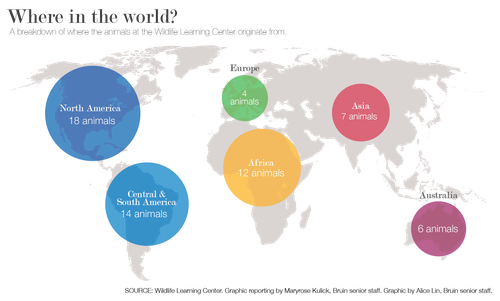

From Zeus the blind western screech-owl to Lola the two-toed sloth, animals at the Wildlife Learning Center provide the public with interactive education about wildlife. The wild-born animals are too injured or dependent on people to be rereleased, and the domestic creatures could not survive in the wilderness.

Wildlife Learning Center co-founders Paul Hahn and UCLA alumnus David Riherd have been rescuing the animals to teach people about biology for more than 20 years.

Hahn and Riherd grew up in different states, but both near pond ecosystems with animals such as fish, snakes and salamanders. As young children, they each spent their free time exploring ponds and forests, they told me, sitting at a picnic table in the Wildlife Learning Center. Two scarlet macaws were perched in the distance, dappled in sunlight.

Growing up in the Midwest, Hahn ventured into the woods and lakes with his outdoorsy family during frequent camping and fishing trips. He created his own animal classes in second grade, inviting the neighborhood kids to the woods and showing them schematic diagrams to teach about morphology, the structures of different species.

Flies buzzed around us and kids babbled in the background as Riherd described his childhood in Altadena, California, at the base of the San Gabriel mountains.

He lived near a canyon with close proximity to hiking trails. Every summer, his parents took him to the Sierra Nevada mountains. His exposure to nature led to his interest in animals, he said. As a child, he caught snakes, volunteered at a local nature center and collected diverse pets – dogs, snakes, turtles, lizards, geese, ducks, goats, chickens, rabbits and pheasants.

“I wasn’t one of those kids that got an animal and expected my parents to take care of it,” Riherd said.

Though he grew up reading animal books for fun, Riherd went on to study sociology at UCLA. To this day he doesn’t know why he didn’t major in biology. “I think I was just kind of a late bloomer and didn’t really realize what I wanted to do,” Riherd said. “But yeah I know, it made perfect sense to be a biology major.”

Riherd decided to study molecular biology in graduate school at Cal State Northridge. He met Hahn in a chemistry class.

“One of us mentioned something about ponds and the other was like, ‘Oh my god, you like ponds? I like ponds too!’ and everyone was thinking, ‘OK these guys are geeking out,’” Hahn said. “That’s when we immediately hit it off that we were both animal nuts.”

The students had a few small pets, like snakes and frogs. They kept the creatures at Riherd’s apartment or in Hahn’s duplex’s garage, which he converted into a place to store tanks for the animals.

The teaching began when Riherd’s friend, a teacher, asked if he could bring the animals to her class and talk about biology. She enjoyed the lesson, Riherd said, and introduced him to the school enrichment coordinator for the district. The biologists then began traveling to about 12 elementary schools in Palos Verdes, California, where each school had a set day of the week to be visited for a three- to four-week period.

"One of our selling points was, ‘Hey, you’re learning about this from biologists,' whereas in the classroom you may have a teacher that doesn’t have a science background at all,” Riherd said.

The more they taught, the more pets they acquired from parents who, for example, no longer wanted their pet turtle. The business was outreach, operating out of a van. Hahn and Riherd began hiring other biologists to help teach, including UCLA alumni like veterinarian Susie Garity.

More than a decade ago, while in graduate school, Hahn and Riherd signed a contract with the Los Angeles Unified School District to visit about five Title I schools a day, five days a week, for four to six weeks. The funding was available for Title I schools, which are failing to meet academic standards and whose students come from low-income families, Riherd said.

“Unlike many of us who are privileged to grow up in areas or have parents that could facilitate natural experience, a lot of these urban kids have never been out of the middle of the city, never been to the zoo, never been to the beach,” Hahn said.

Teaching is special for Hahn because his lesson could be a child’s first interaction with nature and inspire him or her to pursue the field. “If they’re a biologist deep down inside, and they’ve never been exposed to the amazingness of nature, all they would see is, 'Oh that’s a difficult subject,’” he said.

In October 2007, the organization moved into a permanent residence in Sylmar while it was still nothing but an old olive grove. They wanted to be close to Los Angeles since they were teaching for LAUSD. The property was previously used for heavy agriculture, so the zoning permitted keeping animals on the lot.

“I was there when everything was just dirt,” said then-co-manager Garity.

Hahn and Riherd built everything on the single-acre property. Riherd planted each of the approximately 1,000 plants. Hahn carved the wooden signs that label different enclosures. Both biologists dug out trenches to lay the plumbing and electricity.

They held their opening party in April 2008, about six months later. But that same year, they lost their contract with LAUSD because of the economic recession. With their biggest source of funding gone, they quickly decided to open their center to the public and create the on-site education program it is today. By investing their own money and receiving help from family, they survived the recession despite bumpy years spending money on their bills, the lease and the enclosures.

Money remains the most difficult part of the business, Hahn said, since it costs $2,000 a day to run the Wildlife Learning Center. However, they get some financial help from high-profile donors, including actress Betty White, who discovered the center while filming and has since donated a veterinary suite. When the actress visits, she’ll sit on the picnic tables and the owners bring her animals.

“What kind of animals does she like?”

“All of them. She’ll hold them in and pull them into her chest and her neck, and she closes her eyes and just swaddles it and kisses on it. We’re all just kind of like, ‘Betty, do you want another animal yet?’” Hahn said.

She even kisses the monitor lizard.

Actress Julia Roberts and her family also ventured in for a visit, sitting in the office playing with baby monkeys for two hours. Riherd stopped to look up at a squirrel. Hahn said the indigenous animals add to the atmosphere.

"You kind of feel like you’re in the woods or at least not in LA,” he said. “If you saw, this is kind of surrounded by neighborhoods and industrial area, so it’s kind of a little oasis.”

Right on cue, a train tooted its low horn, drowning out the sparrows’ chirping for a moment before the serenity was restored.

It was just like she had never left.

When Susie Garity came home from veterinary school every eight months, her first stop was the Wildlife Learning Center. The owners gave her the keys and she went straight into the serval enclosure, picked up Kodi and held the lynx like a baby.

Garity graduated from UCLA in 2005 with a degree in ecology, behavior and evolution. She knew she wanted to work with animals, so she applied to the Wildlife Learning Center after seeing a job listing online. By the time Garity left for veterinary school in 2009, she was a co-manager who had fallen in love with the cats at the nonprofit organization.

Garity grew up in a broken home in the Inland Empire, she said. She had a rough life, and her cats were her only real friends, namely her orange childhood felines September and December.

"I would say I’ve always preferred animals to humans," Garity said. “When you grew up and you don’t really know what love is, it’s hard for you to trust people.”

She thus had an inclination to work with cats at the Wildlife Learning Center when she started as a wildlife biologist and educator. Her job included primarily animal care – husbandry and training – and conducting education and outreach programs at schools and parties.

A few months after Garity started working, the center acquired Tag the serval, a spotted African cat. He was distrusting and required a lot of patience.

"He wasn’t the friendliest of critters, and I kind of decided I was really going to get to know him and work with him,” Garity said.

The goal was to have him be an educator and ambassador animal, so she had to train him to walk on a leash. Though he eventually cooperated, his initial response was to roll on the ground, claw, bite or try to play – and wild animals’ play can quickly turn into aggression, she said.

Garity’s other favorite cat is the lynx Kodi, who she raised since he was 6 weeks old.

Kodi was shy at first, but she stepped up as surrogate mom. She took him home with her at night for several months because he needed nursing care, and there was no one at the center over night. It was an opportunity to bond, and since Kodi wasn’t weaned yet, she worked on hand-feeding him and teaching him not be aggressive toward food.

Over a process of several weeks, she worked up to putting a collar on him, first placing the collar near him, clicking it near him, laying it on his neck and finally putting it on.

Garity spent extra time hanging out with the cats, sitting outside their exhibits so they would get used to her and accept her. They reminded her a little of herself, because she understood their distrust in people.

“I’m more reserved, too,” she said. “I got them.”

Both Tag and Kodi were certainly challenging, she laughed through tears.

"If I didn’t end up at the Wildlife Learning Center and specifically didn’t meet Tag, I probably wouldn’t really know what love is,” she said. “I definitely love those cats. We saved each other.”

##Stepping into the island jungle

We toured the Wildlife Learning Center on a sunny October day, beginning by the picnic tables under an overhang decorated with twinkle lights. Small children ran by screaming, “Cheetahs!” after seeing the serval exhibit.

The nearest enclosure housed Nanuck the Arctic fox, who sometimes chases her red fox co-inhabitant. Before she was rescued, she was destined to become a fur coat. The lemurs, which sometimes sit in the sun and meditate, came from an Indiana zoo.

Porcupines munched on carrots and chunks of watermelon rinds in their tin-roofed enclosure. Two blond boys leaned on the rope outside, waving to a baby porcupine waddling behind the chain link fence.

Hahn and Riherd led us inside the exhibit, which guests can enter during onsite interactive tours.

We noticed a porcupine climbing up the fence baring its orange teeth.

“That’s rust,” Riherd said.

Hahn handed us leafy ficus branches to feed to the quilled creatures. They stood up on their hind legs and curiously leaned toward our outstretched arms. More chubby porcupines wobbled to us like Winnie the Pooh. Hahn reached down to pet one in a front-to-back motion to avoid an unfortunate encounter with the quills on its lower back. Riherd said petting their straw-like fur makes him too itchy.

The baby porcupine, which was born at the Wildlife Learning Center, stepped on my feet and gently lifted his weight onto my leg and began climbing me like a tree. His claws – luckily relatively dull – firmly pressed into my shin before Hahn picked him up by his two front paws and pulled him away.

“Aren’t they charismatic and awesome?” Hahn said.

The founders started listing the names of the spiny animals – Walter, Betty, Alan, Freddy, Gerdy and Gus Gus. “Like Cinderella?” I said.

“Yeah, that’s where it came from,” Riherd said.

We moved further through the center past the big-eared fennec foxes toward the bald eagles, which were injured in the wild. As for the alligator named Fluffy, he lived in a bathtub before and now basks in the Sylmar sun.

“He doesn’t look like it, but he’s fast,” Hahn said, looking at the reptile’s dark unfocused eyes. “He’s looking at us.”

They explained that alligators whip their powerful tails to protect themselves and their babies.

“Which is rare in reptiles,” Riherd added.

We moved closer to the front of the property toward the prairie dog habitat. The furry animals bobbed up and down, jumping against the glass and making a screeching sound while trying to burrow.

“I want one!” my friend said.

“No you don’t,” they said at the same time. “They’re biters.”

The tortoises are friendlier and don’t bite – as long as you don’t visit them with your toenails painted red, resembling strawberries. Back at the red picnic tables, we passed by the perched red macaws. They are strongly bonded and fell in love, Hahn said. He likens them to an old married couple.

Our last stop on the tour was the reptile house. A Brazilian rainbow boa was cozied up in its glass tank. Nearby lives a Burmese python that’s frequently compared to the one in Britney Spears’ 2001 MTV Video Music Awards performance.

They also have a giant bullfrog the size of a football.

“Do you know what we feed it?” Riherd said. “Mice.”

The founders took us into the back feeding room, filled with shelves of dishes and white boards with feeding scheduled laid out; “a.m.” schedules were written in blue marker and “p.m.” in green. The boards listed the different animals – Boomer, Sage, Newton, Zeus – with the appropriate grams of food next to them.

White bins full of biscuits lined the wooden floor adjacent to freezers full of mice and rats for the carnivores.

One shelf stored buckets of live mealworms and chirping crickets. A shelf above contained enrichment spices like Trader Joe’s cinnamon that get sprinkled into the habitats; the new scents simulate a real, investigable environment. The top shelf held empty toilet paper rolls and a Coca-Cola cardboard box, in which the biologists hide food to provide more challenges for their animals like they would encounter in the wild.

We left the reptile house and met two final animals.

“You’ll like meeting Boomer,” Riherd said.

“Would you mind bringing me the Gila and a pair of gloves?” Hahn asked an employee.

“Come on buddy, “ Riherd said, coaxing Boomer the lynx out of his enclosure. “Wanna come out?”

The black-tailed cat was bred for the pet trade in Oregon but went unsold.

Hahn brought out their Gila monster, a lizard that was an illegal pet before it found a new home at the center.

“Can you see his tongue?” a mom asked her kids, who were examining the Gila.

Hahn and Riherd never imagined when they started bringing their van of animals to classrooms that now they’d be running a nonprofit organization with about 100 visitors a day. They’ve delivered about 24,000 presentations so far, Hahn said.

The most important part of the Wildlife Learning Center is the education component, Garity said. She hopes the animals can impact children and get the respect the critters need.

"It’s important for people to be able to get up close and personal and be able to really understand where these animals come from,” Garity said. “Animals are life-changing if you kind of let them in. ... They give you something, and they touch your soul in a way that changes you.”