Before there is any discussion on the future of sustainability, there is one premise that must be undeniably accepted: Within our generation, humankind will experience the consequences of global warming.

The science is sound.

Nearly all climate scientists – 97 percent – agree that global warming is occurring and will continue to occur, and the question has now shifted from “How do we stop this?” to “How do we live with this?”

“Thriving in a Hotter Los Angeles” is UCLA’s answer.

The university has essentially taken a who’s who of people that did better than you in class and streamlined them into a team of talented researchers focused on “achieving 100 percent sustainability in energy, water and biodiversity by 2050” in Los Angeles.

While the title is appropriately cinematic – given the city we live in – the project fits in perfectly with UCLA’s self-prescribed vision of itself as a revolutionary institution committed to social change.

However, after reading through the various sections of the initiative’s flashy-looking website, and especially after perusing its “components” section, I came away with one notable criticism: I still have absolutely no clue what this future Los Angeles would look like.

There’s a lot of fancy-sounding jargon and great ideas – yes, I would absolutely love to see the university “develop new materials, devices and large-scale products to efficiently capture and store ambient energy as electricity” – but we’re still in the dark about what exactly the future entails.

So, fully acknowledging that I do not have a fancy title associated with my name (“world’s best son” doesn’t count, Mom), I have put together a small blueprint using existing green technology – and keeping in mind the spirit of the grand challenge – for what a completely sustainable Los Angeles would look like in 2050.

Downtown

By 2050, downtown Los Angeles will have made its official transformation from urban blight to culture center.

Future Angelenos can grab a bicycle from Metro’s bike share system (construction is set to begin in fall 2015) and cruise down the Figueroa Corridor. With its wide sidewalks, physically separated bike lane and dedicated bus corridors, it will be the perfect north-south route for the important businessperson or trendy coffee shop barista.

Or, after finishing a hard day’s work at City Hall, scrappy young UCLA interns can hop onto a fully electrified streetcar and follow its route down to the bars at L.A. Live and watch the Los Angeles Clippers take on the Cleveland Cavaliers in the 2050 NBA final (the Los Angeles Lakers, sadly, are still waiting on Kobe Bryant to retire).

After de-stressing, the young professionals and urban denizens of downtown Los Angeles can hop onto any of the city’s dedicated rail lines and take it to the sprawling suburb of their choice: Purple Line to Westwood, Expo Line to Santa Monica, Gold Line to East Los Angeles or even the Blue Line to Long Beach.

Meanwhile, high-rises will have come to dominate the landscape around downtown. A stroll down Figueroa Street, Flower Street or Pico Boulevard will feel more like Manhattan than Queens, and each building will power itself through city-mandated investment in transparent solar panel glass – a technology currently under development at Michigan State University.

Beyond that, there are plans to re-green concrete “parks” like Pershing Square, and to install a park over the 110 Freeway that will cap the highway and reconnect “old” downtown with “new” downtown. These plans will make the city center an immensely walkable place, so much so that the city will decide to cash on its newest currency: foot traffic.

Special sensors underneath the widened sidewalks will capture the mechanical energy of the masses of people that traverse them everyday and use it to power our streetlamps at night – a similar project already exists in some poorer neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro.

The Westside/Mid-City

Outside of the new, shining urban core of downtown Los Angeles, the real challenge lies in taming the rest of the city's sprawl, with its narrow, congested streets, its thematically and ethnically disconnected neighborhoods, its resistance to densifying and its horribly narrow sidewalks. All of which adds up to one conclusion: This is going to be hard.

In UCLA Grand Challenges, the researchers posit that every house in Los Angeles will have solar panels by 2050, which – given the growth of the solar energy market (41 percent in 2014) and Los Angeles’ 330 days of sunshine – is correct and important. New housing regulations, such as insulating weather strippings, will ensure houses use less energy overall, but the largest – and most noticeable – aesthetic change will be in the lawns.

It’s hyperbolic to say the green lawn will disappear – this is America, after all – but there will be a large number of “desert gardens” that are more appropriately suited to Southern California’s drier climate. Los Angeles is in fact not a desert – it has a mediterranean climate. But still, too many people use too much water for everyone to sustain real lawns. So a bike ride down Veteran Avenue will have a less green hue in 2050.

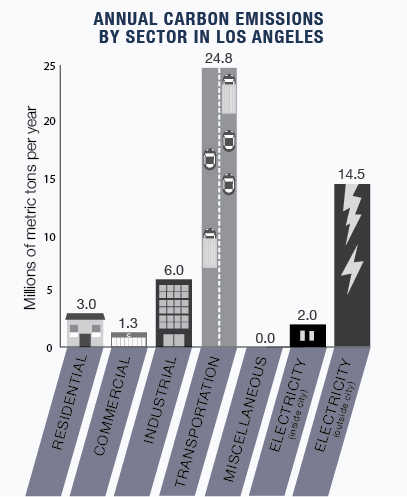

The funny thing is, though, housing  isn’t Los Angeles' largest problem in terms of carbon emissions. Of Los Angeles’ nearly 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emitted each year, 24.8 – or almost half – comes from transportation. Which is both surprising – we have a lot of people and houses – and not, because everyone drives. So in the congested, scary, narrow, transit-dead Mid-City and the Westside, some things will have to change.

isn’t Los Angeles' largest problem in terms of carbon emissions. Of Los Angeles’ nearly 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emitted each year, 24.8 – or almost half – comes from transportation. Which is both surprising – we have a lot of people and houses – and not, because everyone drives. So in the congested, scary, narrow, transit-dead Mid-City and the Westside, some things will have to change.

First, two of Los Angeles' most iconic (and congested) streets – Olympic Boulevard and Pico Boulevard – will have been redone. As suggested in the RAND Corporation’s Moving Los Angeles: Short-Term Policy Options for Improving Transportation study, both will be required to turn, essentially, into one-way streets – Pico Boulevard running east and Olympic Boulevard running west. Not only will this open up another two lanes of traffic, but it will also create enough space to run a dedicated right-of-way bus service, with attached electrical wiring overhead to ensure the buses can traverse the entirety of the city’s sprawl, like in San Francisco.

Additionally, protected bike lanes will be installed along the busy north-south routes – think Fairfax Avenue, Veteran Avenue, Westwood Boulevard, etc. – that will enable people to seek an alternative mode of transportation with more than just a painted white line as protection.

Up in Hollywood, plans will have been completed to cap the 101 Freeway – like suggested earlier in downtown – and a larger Hollywood Park will serve a reconnected community and create a more livable, walkable Tinseltown.

However, capping freeways isn’t an option in a lot of places – and especially not on a freeway like the 405, which is entirely above ground. For the world’s most congested freeway though, the horizon over those sound walls is about to look a lot more organic.

In Switzerland, a group of algae farms have been attached to freeways in order to have them “eat” the CO2. A steady diet of L.A. car carbon dioxide and sunlight will create pristine conditions for the algae to grow and be harvested for other sources of energy – like electricity.

The Valley

While there are a whole host of other communities in the L.A. Basin that we can’t get to – Long Beach, the beach cities, Pasadena, the Eastside (the real one, across the river) and South Los Angeles – the good news is that for all of its racial, ethnic, financial, you-name-it diversities, the L.A. Basin, structurally, is very uniform.

At its core, it’s essentially an arbitrary association of low-rise buildings, strip malls, and neighborhoods intercut with long boulevards that serve as centers of commerce, which means that, generally, the solutions are going to be the same in each of the neighborhoods.

But journeying over the hill, there are the forgotten suburbs of the city – carved directly out of the dreams of a Stepford wife, filled with cookie-cutter houses and large streets, where each passing day feels exactly like the last.

I’m talking about the San Fernando Valley – an environmentalist’s worst nightmare.

The San Fernando Valley of 2050 will not have tamed its sprawl – that much is impossible at this point. But special, dedicated bus lines running down the major throughways – Reseda Boulevard, Topanga Canyon Boulevard, Van Nuys Boulevard, etc. – will serve Metro’s Orange Line and feed people to the refurbished Warner Center in Woodland Hills aka the San Fernando Valley’s new “downtown.” Construction is underway there now and will continue to feed a development craze that has so far subsisted on the rich and suburban of Malibu and Calabasas.

A new subway running down Sepulveda Boulevard that’s parallel to the 405 Freeway will be a boon for commuters and especially for UCLA students from the San Fernando Valley looking to go home for the weekend.

A new subway running down Sepulveda Boulevard that’s parallel to the 405 Freeway will be a boon for commuters and especially for UCLA students from the Valley looking to go home for the weekend.

But the biggest change will come on the road. The San Fernando Valley’s wide streets are particularly useful for a unique solution: solar roadways.

Solar roadways are being developed by a team of entrepreneurs in Idaho, who are creating a type of textured glass that essentially doubles as solar panels. The flat, straight streets of Los Angeles’ forgotten side would provide pristine conditions for installation and would effectively serve as a giant solar panel for the city and county. These, along with some of the common-sense solutions offered above – gardens more conducive to the environment, water conservation, transit expansion and denser neighborhoods – can create a San Fernando Valley unthinkable today.

♦♦♦

What’s described above is essentially a trailer for the future of the city of entertainment. It shows the potential but can’t possibly provide a large enough picture to truly encapsulate the city 35 years from now. There will be hard conversations about water and resource sharing, not to mention a whole host of technological advances we cannot yet fathom.

And, of course, it will take money. Lots of money, actually. But the exchange rate between willpower and the dollar is skewed hugely toward the former – all it takes is a concentrated effort to make this come forward. UCLA is already doing a lot of reasearch, but the ideas can’t end at Le Conte and Gayley avenues.

There’s no smoking gun that will lead us to sustainability. It will take an approach that’s as varied as the neighborhoods it seeks to serve, and – as high as the real costs are – in a region of more than 12 million people, the human costs of failing to act may be even higher. ■