Part IV: The way home

Quite frankly, there isn't a lot that nonprofit organizations and private charities can do to directly end homelessness. It’s simply beyond their scope. So it’s up to the city, county and state governments to invest in measures to house the people on the streets.

Unfortunately, the local government’s response has been a joke.

After months of debating what should have been a no-brainer, Mayor Eric Garcetti declared a state of emergency for homelessness in early December. The declaration came with $12.4 million of emergency relief funds to keep homeless individuals out of harm’s way during the El Niño season.

But again, it’s like putting a Band-Aid on a gaping wound. The city council’s attempt to declare a shelter crisis and expand shelter capacity was a disaster. The council members debated about bylaws and bureaucracy instead of securing a concrete source of funding for housing. As the Los Angeles Times editorial board described it, the "whole process has been more of a turgid civics debate than an urgent response to a desperate situation.”

The city needs to rise above quick fixes and empty gestures if homelessness is to subside anytime soon. According to Toby Hur, a field education faculty member at the school of public affairs, government leaders cannot remain complicit in the problem by ignoring it – he lamented the police crackdowns and revolving shelter doors.

Most of all, both Hur and Thomas expressed disdain for “right to rest” laws. These kinds of laws, which became popular in the 1980s, affirm homeless people’s rights to engage in everyday activities (such as eating and sleeping) in public spaces like parks. It’s a well-intentioned effort, but it’s enabling and fails to actually make homeless people’s lives better, according to Thomas. It lets people remain on the street.

Even shelters are only a temporary solution. People can usually only stay for a month or two, and then it’s back on the streets.

By contrast, supportive housing is an effective and economical way to serve the homeless population while addressing their complex needs and situations. A 2004 study by the Lewin Group found that permanent housing for a homeless person in New York would cost $41.85 per day, compared to $54.42 for a shelter and $74 for prison.

Another big part of the equation is the system of state psychiatric hospitals, which care for people with mental illnesses.

It’s the best option for those with serious psychiatric disorders who find it difficult to access the resources they need from society to receive long-term shelter and care. Between 2009 and 2011, the state government cut $587.4 million from its mental health services budget, which funds institutions like psychiatric wards.

The cuts were part of a process called "deinstitutionalization," which sought to release patients from state psychiatric hospitals in order to better integrate them into society and save state money. However, as John Martin said in the Schizophrenia Digest, that experiment has been a massive failure which has left people with serious mental illnesses to fend for themselves.

The cuts need to be reversed if the state wants to get people with mental illnesses off the streets for good. Extra funding will go a long way toward improving the quality of care provided and oversight to prevent the abuse that can sometimes take place in state psychiatric hospitals.

The fate of these institutions depends on the support of the state and local governments, which need to plan for and fund supportive developments.

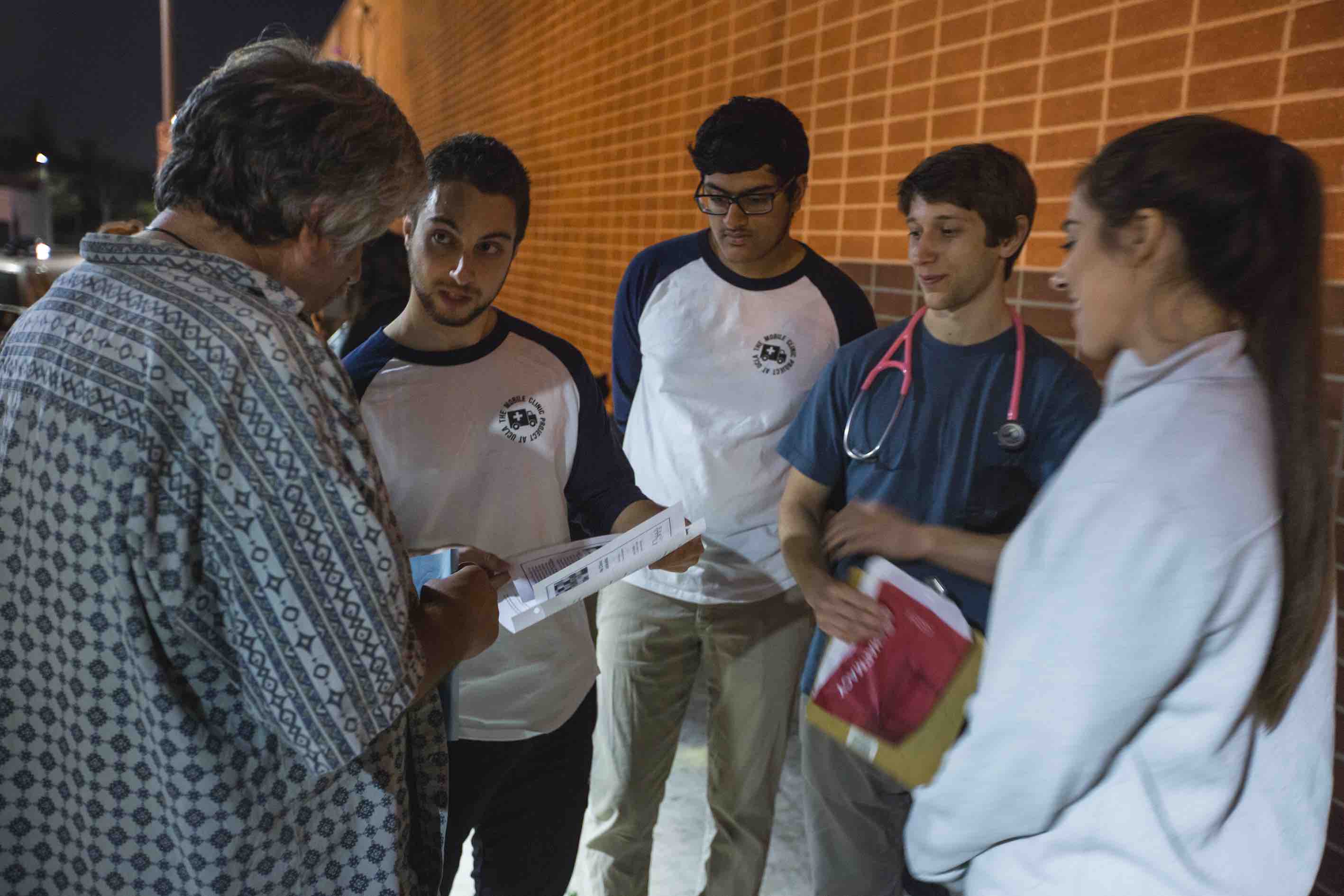

So yes, ending homelessness is far beyond the scope of what the BID, Bruin Shelter, Mobile Clinic Project or any other nonprofit could ever hope to achieve. But that doesn’t mean they don’t play vital roles. Every person housed temporarily or given supplies is a step in the right direction, but the true purpose of these nonprofits is to draw attention and get the locality involved in the issue. In this respect, the advocates may have finally reached a breakthrough.

Los Angeles’ by-now notorious reputation as the “homeless capital" of America has prompted the city to approve a plan with an estimated cost of $1.85 billion to build permanent supportive housing developments over the next decade. The California State Senate is also working to pass a proposal to dedicate $2 billion to construct new housing statewide, in a move that Los Angeles Times reporter Gale Holland described as “the most sweeping from the state in a generation” and the Daily Bruin's editorial board called “unequivocally, a good thing.”

This is good. This is progress. But there needs to be even greater investment in supportive housing if the government wants to make a substantive impact on homelessness.

And the local nonprofits still have work to do. They need to continue casting light on an issue that has crept under the radar for decades, because their efforts are starting to work.

“The local government and business response is far different now that it was 11 years ago,” Hur said. “People are finally starting to pay attention.”

I thought back to Thomas’ story about Bob, the man who spent 25 years on the streets of Westwood.

Thomas was right. It doesn’t have to happen.