Conservative commentator Ann Coulter referred to us as “Mandarins” last week, inciting furor online. This past winter, Chinese American groups rose up in a sea of protests seeking to reduce or eliminate punishment for Peter Liang, an Asian-American cop convicted of manslaughter in February regarding the killing of Akai Gurley, an unarmed black man. In addition, the second Asian American centered television show ever, Fresh off the Boat, was partly through its second season run. Despite all that, at UCLA, I’d heard or read nary a response to the Liang trial in particular from any of my friends, both those involved in culturally and ethnically oriented organizations or otherwise. Liang has since been sentenced to 800 hours of community service and five years probation – and no jail time.

To the 2013 UCLA admissions committee, my 17-year-old self seemed destined for integration into the social justice space that is the Community Programs Office. In my application essay, I wrote about how I hated calling myself American. I recounted my yearslong placement into additional elementary school English as a Second Language classes, even when English was my native tongue. In short, I wrote about how it means to be the “other” in U.S. society.

Despite mellowing considerably from exoticized, “other”-tinged angst since college applications senior year of high school, the word “American” still felt clumsy on my lips while studying abroad in Europe over this past summer. Local men off the Cote d’Azur in France catcalled, “Ni hao, ni hao.” A man on the bus asked me and another Asian female friend if Hong Kong was in China or Japan. Ah, to be a perpetual foreigner, even abroad.

In reality, however, the admissions committee missed their mark. I committed to the pre-medical track instead. Although the social justice and pre-professional pathways are not mutually exclusive in theory, in reality, they often are. The rigors of the lower division life science prerequisites turned my life into sequential rounds of drinking scalding hot Kerckhoff coffee and staring sadly at textbook pages on Friday nights. Even in the writing of this article, interviews and other research were put on the backburner while I studied over 20 hours a week for the MCAT this past winter.

In my own experience, both the international Asian and Asian-American students have tended away from being "woke," or aware of sociopolitical issues, both pertaining to racial or ethnic issues and other aspects of identity and class. I often feel like my casual musings about the model minority myth or other happenings both online and on campus fall on deaf ears. In fact, while writing my University of California application essay in high school, other Asian students were those who most strongly objected to my identification of myself as a person of color.

At UCLA, the situation hasn’t seemed to fare much better. “I didn’t know you were an activist, Kelly,” remarked one acquaintance over Facebook. The conversation about organic chemistry had taken a detour into my outlook on the privileged experiences of many Asian-American students who grew up in primarily middle class Asian communities and attended Asian-majority high schools. I wouldn’t call myself that, but to this person in particular, even voicing innocent incredulousness at the sheer level of sheltered privilege some of these students had constituted “activism.”

Why don’t Asian Americans on campus care about politics?

The wording of the question is itself loaded, presumptuous, overgeneralized and probably highly offensive. The term "Asian-Americans" is not truly all-encompassing – there are East Asian people, Southeast Asian people, Pacific Islanders, South Asian or Desi people, mixed or hapa people and so on. The directors of Asian Pacific Coalition, Priscilla Hoang, a third-year sociology and public policy student, and Jeffrey Hsu, a fourth-year sociology and film student, I soon discovered, prefer the term Asian Pacific Islander Desi American, or APIDA. Still more people, involved in social justice or otherwise, use the census-based race category of Asian-American and Pacific Islander, or AAPI. I won't claim to be highly inclusive of the South Asian community on campus in this article, as the focus, inspired by the Peter Liang trial, is more on AAPIs.

Demographic labels aside, what does it mean to “care” about politics? What is considered political awareness?

With the Peter Liang trial and ensuing protests by Chinese-American groups in mind, I set out with intent to characterize the state of AAPI activism and political involvement on campus, and possibly explain why the dynamic stands as it does. Was the perception of political apathy within UCLA’s AAPI population misplaced? After all, AAPI-identified students make up over a third of the undergraduate student population, not counting international students, both those possessing citizenship from Asian countries and those doubly-removed, but phenotypically appearing AAPI, like two Canadian students of Chinese descent whom I happen to know.

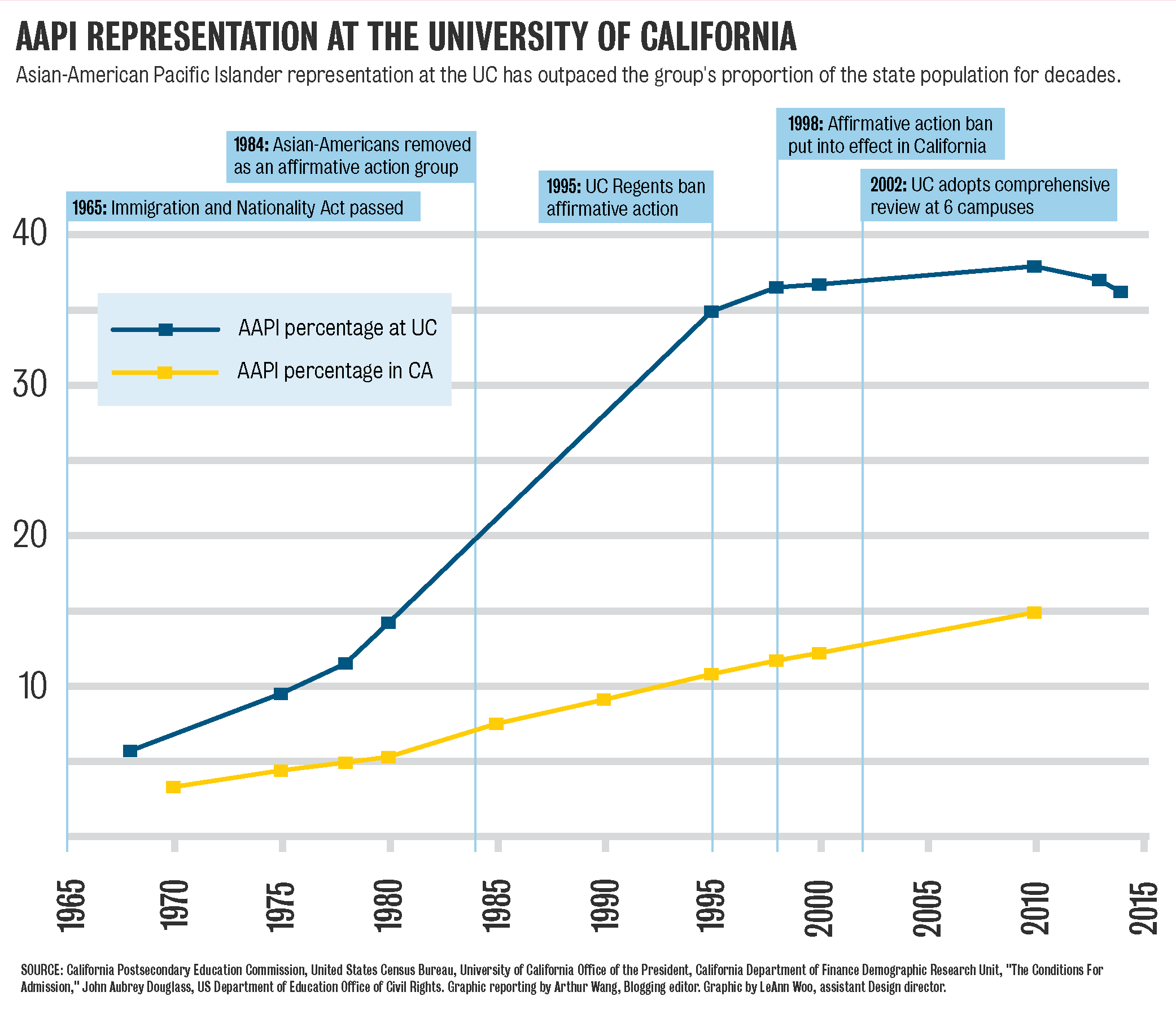

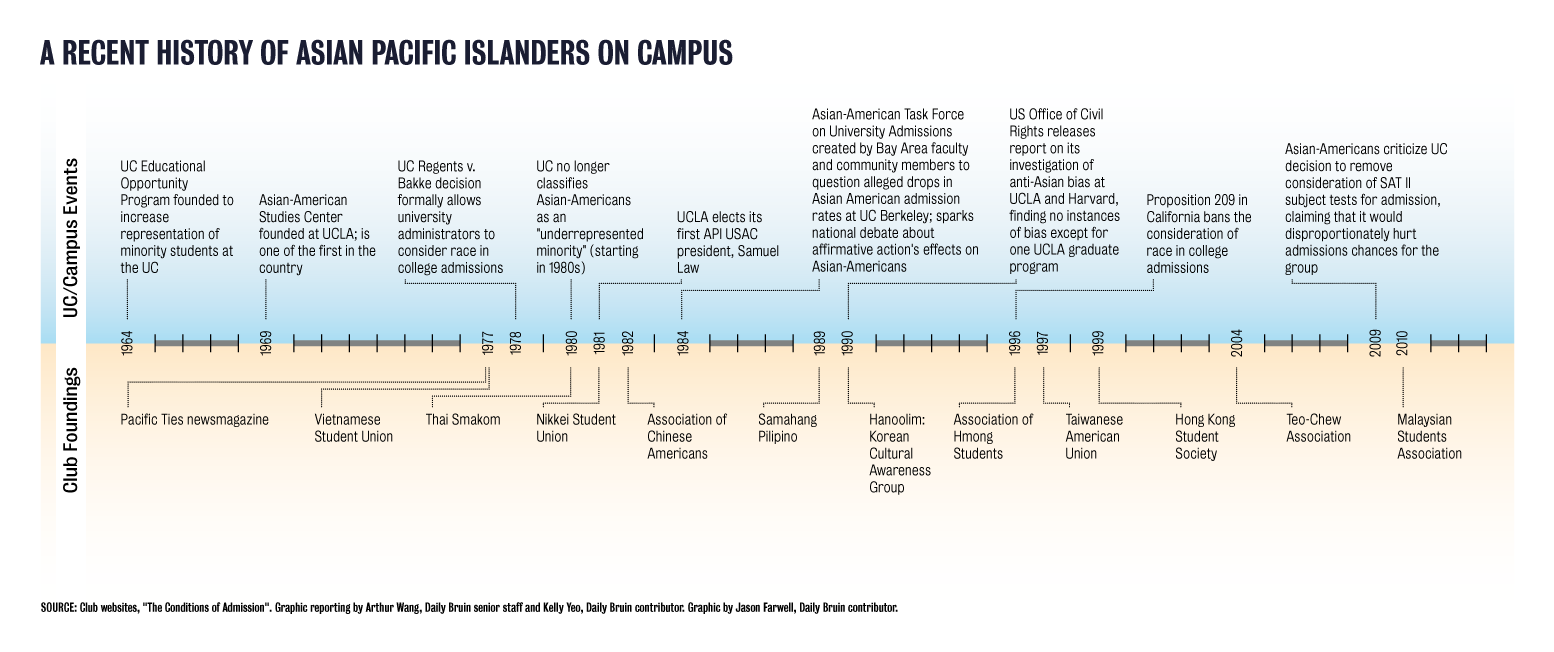

For many students, it’s difficult to believe a campus of which Childish Gambino rapped, “Asian girls everywhere” was once anything but AAPI-predominant. In fact, the APC, founded in 1971, was initially created in order to address underrepresentation of East Asians on campus, according to APC directors Hoang and Hsu.

As they readily admit, APC’s efforts had little to do with the demographic shift. The changing demographics of California, the increase in admissions standards, and ultimately, the abolishment of affirmative action through California Proposition 209 helped create the admissions environment that has led to Asian and Pacific Islanders being the largest demographic category on campus at 33.5 percent, compared to nationally hovering around 5 percent and 13.5 percent in California, if Pacific Islanders are excluded.

Clearly, underrepresentation is no longer a huge issue. For AAPIs as a conglomerate, it never has been.

Many of today's cultural organizations are vastly different from those that the founders began. Perhaps spurred by overrepresentation on campus, many AAPI students participating in cultural organizations tend to view these affiliations purely as social contacts. The Association of Chinese Americans now has hundreds of members, and like other organizations such as Vietnamese Student Union, maintains several smaller organizations within themselves such as dance teams. Full disclosure: I joined ACA in the fall of this year, primarily for the boba discount at Volcano Tea House, and attended a town hall organized by ACA in winter quarter for this article.

In connecting with both more politicized and apolitical groups, many people understandably were hesitant to speak on behalf of their group's involvement in campus politics, the CPO, and Undergraduate Students Association Council. Perhaps they were also afraid of their comments being construed as representative of the AAPI community as a whole. With them, I felt the ever-present lingering need of those identified as members of minority groups to act as their group's best representatives.

Perhaps among the most hesitant were the directors of the APC. APC is the appointed political organization for APIDA involvement on campus. A mother organization within the CPO, or one of many organizations aimed at minority access and retention that operate out of the Student Activities Center, APC's initial cause of addressing underrepresentation of Asians on campus is now a moot point. Today, the relatively small group has focused their energies in recent years on joint efforts such as passing the diversity requirement.

Under the umbrella of APC are 24 organizations, including ACA, although many general members of these organizations are unaware of the coalition's existence. Both Isabel Qi, a third-year earth sciences and geography student, and J.R. Nasaharat, fourth-year psychology student, community empowerment chair of ACA and director of Thai Smokam's Thai Culture Night, are aware of their organizations' affiliation with APC, though have rarely attended the meetings.

The reality is that many of UCLA's AAPI cultural organizations today simply have lost touch with their politicized roots. From dance teams to organizing and acting in cultural nights, these groups have shifted their focus from having their voices heard on sociopolitical issues to becoming a means for AAPI students to socialize around a shared culture.

Qi pins this social focus down partially to diversity in the membership base. Although bound together by an appreciation of Chinese culture and affiliation with the Chinese-American identity, Qi feels there is lack of discussion about larger political issues and Asian activism within ACA.

"We try to push for it, but it just doesn't generate a lot of attention or discussion. I don't think I can really speak to Asian-American activism on campus, since I'm not really informed or aware of that kind of stuff," said Qi. However, she adds the leadership wanted to move towards having more discussions, as shown by the organization of the town hall event this past winter.

Nasaharat says his organization tries to stay as neutral as possible to avoid political backlash. He doesn't consider himself much of an activist, he states, citing his busy schedule as to a possible determinant in his lack of investment in AAPI political issues.

"Maybe after Thai Culture Night, that will change," he said, half-jokingly.

Another organization under APC, Asian Pacific Health Corps, has remained largely uninvolved in the coalition, according to Melissa Chan, a director within APHC. Chan, who is also involved in China Care Bruins, says both organizations avoid involvement in political issues to keep the focus of their missions on helping underserved Asian communities through health fairs and screenings and helping Chinese orphans retain their culture, respectively.

What's to blame for this lack of politicization? Lack of time and motivation may be a key factor. For many students, AAPI or otherwise, a regularly jam-packed schedule at UCLA prevents even the essentials like eating proper meals and sleeping enough. Getting involved in political efforts, whether through joining ethnic organizations or working within USAC, or staying updated on current national or state-level political issues may fall by the wayside in light of merely keeping oneself afloat academically and staying sane.

As always, there are stereotypes abound about matters concerning Asians and academics. According to a 2014 sociology study on AAPI students, AAPI students consistently outperformed students of other racial or ethnic identities, including after controlling for socioeconomic status. The researchers attributed this to the self-selecting nature of AAPI immigrants who then go on to instill a sense of motivation and work ethic. While obviously not a negative stereotype, results such as this study contribute to the model minority concept.

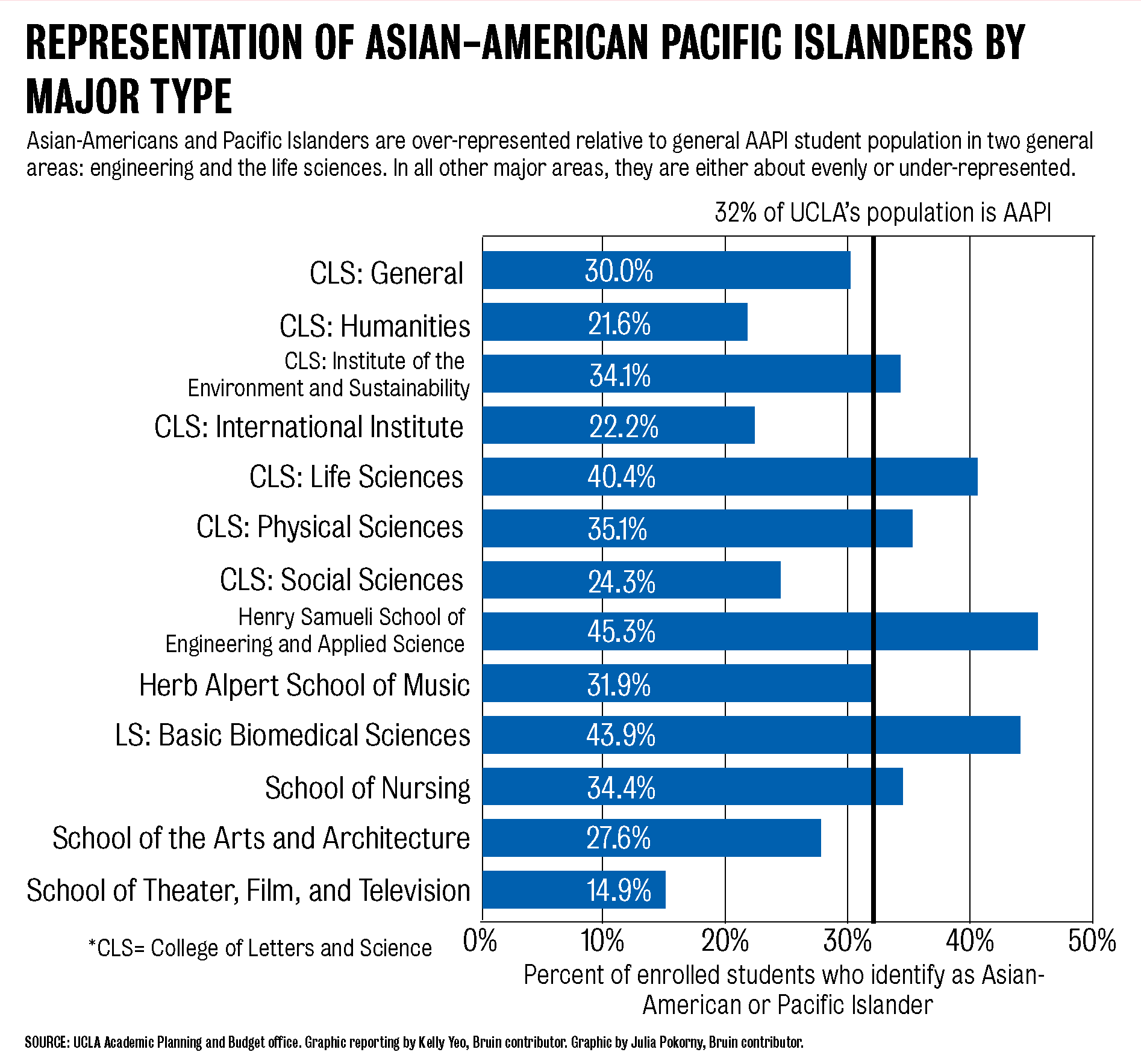

This emphasis on education as the path to socioeconomic mobility may be influencing AAPI students' choice of major. Relative to the proportion of the general student population that identify as AAPI, Asians are overrepresented in only engineering and the life sciences. As of the 2015-2016 academic year, AAPI's made up 45 percent of the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science, and 40 percent of those categorized under life science majors in the College of Letters and Science. Long nights spent studying time-intensive science courses could be contributing to a lack of time or motivation in regards to political participation.

Some AAPI students, however, construe their work through an activist lens. Nicole Nguyen, a third-year molecular, cell and developmental biology student, participates in Vietnamese Community Health, an organization with the Community Service Commission. Although VCH strives to remain apolitical, she considers her outreach work in targeting the underserved, largely uninsured Vietnamese community in the greater Los Angeles area as a form of giving back to her Vietnamese roots.

Chloe Pan, a second-year international development studies and Asian-American studies student, also considers her role in organizing ACA's aforementioned town hall as a means of trying to shift the focus of ACA back onto the political. At the event, attendees spoke about what aspects of identity they felt most and least aware of, in what Pan calls an "identity globe" activity. The aim was to make participants more aware of their privileges and the multifaceted nature of identity.

For Pan, such activities help contribute to a climate on campus that is cognizant of social justice, even if the AAPI population as a whole remains largely uninvolved in political activity both on and off-campus.

"It was actually (AAPI apathy) that made me and Yong-Yi (Chiang, the co-organizer,) want to organize this town hall," Pan recounted. "Not everyone needs to be at rallies or occupying Murphy Hall, but being cognizant of biases that exist is really crucial. Even if you're a STEM major, really taking advantage of the diversity requirement, rather than just viewing it as another requirement, gives you a chance to explore what diversity really means."

How about those who are involved politically on campus? Trent Kajikawa, the 2015-2016 academic affairs commissioner and one of two AAPI council members in undergraduate student government this year, offers that our views on activism and AAPI leadership should go beyond formalized structures.

"What if their community responsibilities are representing their communities in the work that they do?" he said, offering his own AAPI-identified roommate who is bound for Harvard Medical School as an example.

Perhaps the decadeslong tradition of some cultural nights like ACA's Chinese American Cultural Night and more recently, Thai Culture Night and Malaysian and Singaporean Culture Night are themselves a form of political action. Through investing time and energy in planning and executing these performances, organizations bring issues like mental health to light through the story arcs that underlie these cultural nights, and in the process, demand and receive physical space that legitimizes these AAPI narratives.

On the national stage, a similar level of “soft” activism is demonstrated by the increasing trendiness of foods such as poke, Spam, seawood and ube long associated with AAPI’s, which has sparked outcry from some AAPI’s. The New Yorker’s Calvin Trillin caught flak for his poem, “Have They Run Out of Provinces Yet?” A commentary on the rising awareness and popularity of different regional Chinese cuisines such as Sichuan, Trillin’s poem and the ensuing outcry demonstrate the tension between America’s newfound appreciation for ethnic Asian food and the stigmatization many AAPI’s have faced for consumption of their individual culture’s cuisine.

Asian Americans are a highly heterogenous group, and the perceived success of some of its members, in what is now termed the model minority myth, has long homogenized the complex reality of the AAPI experience. Asian American studies scholar Erika Lee divided Asian-Americans into two groups whose experiences with systemic racism have differed greatly: those who immigrated after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act and those whose legacy in America dates back long before that. Given the degree of diversity within the group, it can be difficult to find common ground or unify politically.

As a whole, AAPI political participation takes the form of the path of least resistance. Nonpartisan efforts to help the underserved and the organization of cultural nights focus more on raising awareness of cultural uniqueness and specific identity issues, rather than calling attention to systemic racism. It’s clear the sociopolitical niche the UCLA AAPI community has found is primarily focused on identity. On a campus that is over one-third AAPI, this niche makes common sense; it’s difficult to feel marginalized when one can no longer claim literal minority status. This unique majority-minority status can also be found at the California Institute of Technology, as well as other UC campuses including UC Irvine, UC Berkeley, UC San Diego and UC Davis.

With such a powerful narrative underlying the idea of AAPI activism and political participation, it comes as a surprise, then, when Chinese-Americans protestors demand justice for Peter Liang in the thousands. Whether you agree with their interpretation of the handling of the case or not, this abrupt break from the narrative underscores the untapped political potential of the AAPI community.

However, here on campus, it’s business as usual, as AAPI issues and political participation manifest in subtler ways, and as individual culture organizations proudly display their heritage in the yearly lineup of spring quarter culture nights. This path of least resistance fits squarely into a cultural dialogue that praises identity politics and has seemingly accepted that the personal is political.

In terms of AAPI activism today at UCLA, the mere existence of AAPI communities and, for Kajikawa, the perceived success of AAPI individuals, seems to stand in place of direct action a la Afrikan Student Union after the Kanye Western incident. Maybe for UCLA, whose overarching culture prides well-rounded – and thus busy – students, these shades of critical consciousness represent the best “activism” we can hope for.